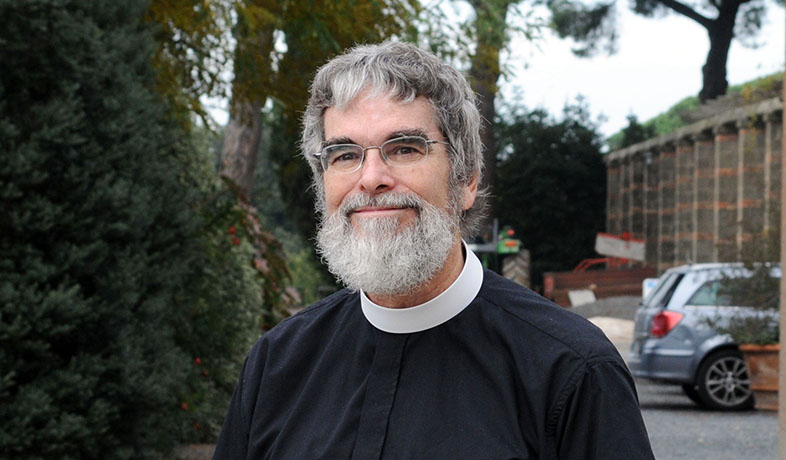

an astronomer and Jesuit trying to bring harmony to the scientists and the faithful

A popular opinion today is that science contradicts religion–that science and religion cannot both be true–and that anyone who claims to believe in both is fooling themselves. One might assume this should only be a problem for fundamentalists, who believe in the literal interpretation of scripture, but it reaches far beyond them. Many religious people in America and Europe today believe there is an inherent contradiction between the ideologies of faith and science, and therefore they logically can only choose one to believe in. This is a false choice. You can absolutely believe in both without compromise, as was the case for most of history. There are religious scientists talking in the public square about this false dichotomy, but you can’t do much better than “the Pope’s astronomer,” Brother Guy Consolmagno, SJ. A well-respected astronomer in the field of planetary science and a devout Catholic, Br. Guy Consolmagno directs the Vatican Observatory and spends most of his time either studying meteorites, or engaging the public on the relationship between faith and science.

Normally, I wouldn’t give so much background on someone in this context, but there are a few unique things that influenced Br. Guy over the course of his life that led him to be so suited to his fascinating, current position.

Brother Guy Consolmagno, SJ was born in 1952 in Detroit, Michigan. His father was a “PR man” and one of the founders of the Public Relations Society of America. Br. Guy grew up with a unique understanding of the relationships between institutions and the public. This exposure to the usefulness of public relations would enable him to excel at one of the hardest skills for a scientist to master: interface with the public. He attended a Jesuit high school, which would ultimately inspire him to join the Jesuit order after spending 15 years in academia developing a robust technique for research of planetary science.

He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he received a B.S. (1974) and M.S. (1975). Amazingly, in his master’s thesis, Br. Guy was the first to hypothesize the ocean of liquid water under the surface of Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa–with the possibility for life to exist there. This happens to be extremely relevant in astronomy right now, as NASA is nearly done developing its “Europa Clipper” mission to travel to the moon and investigate just that hypothesis, almost 50 years later.

Br. Guy attended the University of Arizona, where he received a Ph.D. in Planetary Science (1978). From 1978-83 he was a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer at the Harvard College Observatory and MIT, where he got very bored with research and worried that he might never find a tenured job.

In 1983, he took a break from academia and joined the US Peace Corps. He spent two years in Nairobi, Kenya, teaching physics and astronomy to the local teachers. Invigorated by the hunger for knowledge of the citizens of Kenya, he returned to teach physics at Lafayette College, in Pennsylvania.

Br. Guy had felt called to his faith and to astronomy at various strengths, at various points throughout his life so far, and had considered becoming a Jesuit many times. He finally joined the Jesuit order in 1989, and took final vows in 1991.

“I didn’t want to be a priest, but I knew the Jesuits had brothers. If I was a brother, I could be a professor, and teach astronomy at a Jesuit school. I was all set to teach, but instead, I got a letter from Rome saying I’d been appointed to the Vatican Observatory. They said to do whatever science I wanted and–oh yeah–they had a collection of 1,000 meteorites that needed a curator.” [SM]

From the time he was assigned to the Vatican Observatory, in 1993, he has researched meteorites, asteroids, and other small Solar System bodies. The Vatican provides a special opportunity, because their collection of over 1,000 meteorites represents every major meteorite fall in recorded history.

He has coauthored two astronomy books: the amateur astronomy book Turn Left at Orion (1989), and the planetary science textbook Worlds Apart (1993). He is the author, or co-author, of four books exploring the different ways faith and science are connected. He edited a book about the history of the Vatican’s involvement in astronomy. He currently has a monthly column on astronomy in a Catholic newspaper, and a purely astronomical radio show on the BBC.

In 2000, the International Astronomical Union honored Br. Consolmagno’s contributions to the study of meteorites and asteroids by naming an asteroid “4597 Consolmagno.” [VO]

The most indicative single factoid about Br. Guy’s impact on the public is his 2014 award for “outstanding communication by an active planetary scientist to the general public,” by the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society [AAS]. They highlight his books, which have made a tremendous impact on amateur astronomers, and have shaped public opinion of science and astronomy; and his dynamic public speaking, giving about 50 lectures a year in the US and Europe to a wide variety of audiences. Although they do not use the phrase “public intellectual”, this award is given to individuals who meet the same standards: they have made a “significant impact on the public” and are an “outstanding communicator of planetary science to the public”.

Now that we’ve got a grasp of who this person is, let’s get to his ideology. Br. Guy is on a mission to bring harmony to two groups: scientists and religious people. He is a devout Jesuit and a respected astronomer. One of the core Jesuit missions is to encourage ecumenical dialogue, i.e. to promote unity between the different denominations of Christianity. This desire to help different groups see their commonalities and find a productive relationship is evident in his goals as a public intellectual. He is aware of the groups of people who think there is no place for religion in science, and vice versa. He believes the groups actually share a lot of their ideology, they just aren’t aware of it. In his work as a public intellectual, he tries to bring this viewpoint to the attention of the members of these groups, for the benefit of the individuals and the groups as a whole.

“By existing, we [at the Vatican Observatory] remind the scientists that religion is not their enemy. Even more, we remind the religious people that science is not their enemy.” [SS]

He understands that the division of science and faith is further divided: religious people who fear science, and science-minded people who reject religion. Although he really has one message to the combined group of scientists and religious people, when he speaks, he is usually talking to one specific audience, and makes arguments targeted at only one of the groups. In an interview with Science, one of the most highly respected academic journals across all disciplines, he knows his audience is science-based and will cater his answers to that group only [SCI]. In an interview with the science journalism YouTube channel Sixty Symbols, he knows there will be some religious people who come across it because of the YouTube algorithm, so he includes a few appeals directed at them, but keeps the majority of responses focused on scientists [SS]. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, he gives a more middle of the road approach, knowing there’s a broad audience for this publication [WSJ].

I will briefly mention his work to change perceptions of the relationship between religion and science within the community of theologians and scientists. From such a unique position, as the director of the Vatican Observatory, he wants to be an example to his academic colleagues, and “bridge the gap” between “the community of all theologians, and the community of all scientists [SS].” He wrote “Space and the Papacy,” published in the peer-reviewed journal Religions, to demonstrate to theologians the relationships that have existed between Popes, Astronomy, and Science [SP]. He also wrote “Science of the Vatican Observatory since 2000,” published in the Journal of Jesuit Studies, to give an update to his fellow Jesuits of the ongoing research and collaborations of the Vatican Observatory, subtly promoting that Jesuit idea of unity between differing groups [JJS]. In these papers, Br. Guy is trying to improve the general perception of the relationship between religion and science within the academic communities of scientists and theologians.

Br. Guy is also the president of the Vatican Observatory Foundation. The mission of the Foundation is “to promote education and public engagement in astronomy, and constructive dialogue in the area of faith and science.” He puts in all of this effort in the hope that he can reach as many people as possible, and that those people will gain a fresh perspective. Even if they aren’t immediately convinced, he hopes to inspire them to start productive conversations with their peers in their own fields.

Let us begin the argument we’ve all been waiting for: how science and religion can actually be so compatible. As humans, we seek answers, truth, and understanding. We do this through religion, satisfying our need for truth. We do this through science, satisfying our need for understanding. These viewpoints can exist in harmony. Religion and science are dealing with the same deep human needs: the need for ultimate cosmic truth–a truth larger than ourselves–and the need for understanding at the level of our human capability–and that’s quite low, to be honest. They are coming at it from such different perspectives, says Br. Guy, but they don’t actually contradict each other.

Religion is the concept of having the full truth of the universe, but not being able to understand it with our human minds; and even though we know we will never be able to fully understand it, we still have the drive to continuously seek to understand it better and better with the methods that come along with our religion. On the other hand, science is the concept of being able to understand the universe with our human capabilities, but that understanding cannot encompass the full truth of the universe; and even though we will never be able to get to that full cosmic truth, we still have the drive to continuously seek to get closer and closer to it with the methods that come along with our science… same diff right?

He is claiming that each ideology has the same needs, truth and understanding, and that they employ really similar ideological methods to fulfill those needs. Most people would say those overlapping methods make them contradict, but for Br. Guy those methods actually weave them together to form a more complete ideology.

Before we proceed, the following quote is included for clarification for the skeptics. He is aware of the necessary division between the material facts of science and faith. He does not intermingle the two outside of their ideological basis.

“Even the best scientific theory is eventually superseded by later work. Moreover, in any event, while it is good that theologians be aware of the latest advances in science, it is certainly not theology’s role to judge or endorse scientific theories. Nor, for that matter, is it wise to base theology on the latest advances of science, since that is a ground that is forever shifting.” [SP]

In the following statements, Br. Guy is appealing to the scientists. He points out that they have to believe in three axioms for their highly logical system, “Science,” to work. He then makes a light comparison to religion for each one. He doesn’t need to do much convincing here, just wants you to see how these axioms are actually shared between the two in a way not many people may have heard before.

- “You have to believe the physical universe is real—it’s not an illusion—that there is actually an underlying reality, no matter how bad our senses are. Not every religion believes that, you know. [Christianity, Judaism, and Islam do.]

- “You have to believe that it obeys laws. Who was the first person to think that there were laws in science? Well what’s the alternative? “Oh the nature god’s doing this, and the nature god’s doing that.” Christianity doesn’t take nature gods, it says there are laws.

- “You have to believe it’s worth doing. That studying the physical universe, even if it’s not going to make me rich, is nonetheless a worthwhile thing for grown-ups to do.

“Those are axiomatic. If you don’t accept them, you won’t be a scientist. [To be a scientist,] you have to take those on faith.” [SS]

Now, for religious people, just add one more axiom: that God exists.

“To me, I choose as one of my axioms–that there is a God underneath, behind, supporting all of this. And with that axiom, I then try to say “What can I say about this God? How does that make sense of this universe? Does this axiom work?” Now, if I come up with a contradiction, my answer is not to throw away the axiom, but to say “I’m about to learn something new.”” [SS]

Religious people aren’t asking scientists to prove the universe is real, or to prove the laws of the universe are eternal, because they already agree on those axioms. The only axiom that is not shared, is the belief in God. Science is always asking religion to prove that axiom. And religion brushes off the request, because proving God exists isn’t the point of believing in God. Under the axiomatic approach, there is no need to prove God exists. The point is to satisfy that need for truth.

“Science is a bunch of human invented explanations for the physical universe. As human inventions, I can always understand them, but they’re always gonna be a little bit short of the truth. Religion are truths that I have to deal with, but that I will never completely understand. And if I ever think that it’s finished and it’s done and it’s all packaged and it can be in a book–it’s dead. That faith is dead. That science is dead.” [SS]

Another deep similarity is that religion and science must both actively seek something to stay alive. They must have faith that they are making progress, even though they will never be done with the work. So if the work is ever “finished,” there will be nothing left to seek. As soon as the scientist thinks their truth is certain, their science dies. As soon as the Christian thinks their understanding is certain, their faith dies. Why would a scientist go to the lab if they felt like they already had the truth? Why would a Christian go to church if they felt like they already understood everything God had to say?

How do you feel? Convinced? I think it’s a pretty solid perspective to have.

Br. Guy has made the point that religion and science exist independently and that neither relies on the other. Another beloved ideology, the political ideology of democracy, does not have such a clean record.

“American politics “uses” religion in the sense that it draws something vital out of it, redefining it in the process as something secular, essentially social—and not at all dependent on the belief systems of particular faiths. In short, liberal democracy takes from religion what it cannot supply on its own: a deep sense of belonging. This may be the great political lesson of William James’ insight that our most profound religious instincts pull us out of ourselves and give us certain, yet unutterable, evidence that we are a part of the whole human family.” – Dr. Stephen Mack [PR]

The “parasitic” relationship between religion and politics is toxic. Democracy has to steal from religion to get one of its fundamental needs for survival: a “profound instinct” of “deep belonging.” How do they do it? Why is this necessary?

“A deep religious sensibility has the power to make us feel a real kinship with others. And kinship tempers self-interest. This kind of “democratized” religion enlarges our sense of justice, moving it beyond a concern for individuals alone toward a personal investment in the well being of our countrymen.” – Dr. Stephen Mack [PR]

For your political ideology to survive, you must make sure the people believe that your system is the best system. For democracy to be the chosen system, the wellbeing of society must win out against self-interest. If individuals feel a kinship with all members of their society, they have a deep care for those members. What is best for your kin is what matters most. Democracy’s famous goal is “liberty and justice for all.” To achieve this ideological goal, democracy must steal the religious instinct of “deep belonging,” and identify as a secular nation “under God.” To get the people to feel good about democracy and want to maximize the well-being of their countrymen, they need to feel a spiritual level of connection to them.

Science requires this kinship, as well, but their noble quest for truth is able to bring them together. The ultimate goal of science is to seek the truth of the universe. We cannot be doing science out of self-interest–for fame, money, superiority–as that would lead us to extreme bias, and away from the truth. Science must be done for the truth– for the sake of advancing science itself, or it will fail. So science will always right itself if it begins to go off the rails, because when everyone else realizes science isn’t providing the truth, their instinct is to get back on track. If science is coming closer to truth, it doesn’t need to steal anything from religion to fix itself. Although, it is naive to think the pure intentions of the pursuit of knowledge are enough to overcome unconscious self-interest most of the time. To make sure scientists feel like they have a responsibility to the truth, they do need to feel a “profound instinct” of “deep belonging,” but not to their countrymen, nor to their field of study, but to the universe itself. And that is a feeling we all have, and is pretty hard to miss.

Let’s take a look back into history for a minute. Br. Guy’s perspective is not new. Religion and science have been intertwined in that way for basically all of history, including the period of time when modern science was invented. I want to provide some historical evidence for anyone who is still thinking that only someone so simple and shallow would believe in or be convinced by such an argument.

It has been a few hundred years since the Scientific Revolution, but scientific reasoning has never stopped evolving. Previously, in the post-classical era, all knowledge came from Greek philosophers and scripture. There was hardly any development of thought or pursuit of knowledge. The Scientific Revolution began with a gathering of all that knowledge from antiquity. The Revolution’s midpoint is commonly accepted to be when Galileo challenged the ancient sciences and published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, that argued for a heliocentric universe and against Ptolemy’s geocentric universe, which had been accepted as truth for 1,400 years. The end of the Revolution is commonly accepted to be the climactic publishing of Isaac Newton’s Principia, an unprecedented interpretation of the universe that included his discovery of the laws of nature. There were many thinkers who became scientists and shaped the origin, the foundation, of Science–but Galileo and Newton are widely considered to be, respectively, the father of modern science and the most influential mathematician of all time.

This period of history was not a triumph of science over religion, as some modern rumors like to claim. In this early-modern period, everyone was religious, especially the top scientists. They were motivated by their faith to make incredible discoveries and push the boundaries of human knowledge and understanding.

“They thought the physical universe was made by God, therefore it is a good thing to study.” [SS]

Galileo was a devout Catholic and was actually friends with the Pope! Newton believed “all forces in nature were actions directed by God,” [LL] and the laws of nature were established by God. This trend of prominent religious scientists persisted and can still be seen in modern scientists. For example, the Catholic priest and astrophysicist Georges Lemaître published a paper in the 1920s that helped convince the majority of astronomers that the universe was expanding, a revolution in thought for cosmology; and in the 1930s he published his novel idea of an explosive start for the universe, the Big Bang theory. [GL] All the while, he made sure to condemn any priest who tried to make any sort of “proof” of religion from these theories. This was a challenge, as the Big Bang theory included a starting point that the entire universe could be traced back to, and a nothingness before that. A lot of religious people were very satisfied with how well this idea matched with religion.

Similar to how religious men have been some of the most revolutionary leaders of science, the “activist theologians” of American political history made similarly grand impacts on American social justice. They were people, Prof. Mack says, “whose religious training and experience shaped their vision of a just society and required them to work for it. They have been key players in some of our most important social reform movements.” [PR] Similarly, some of the most influential scientists of all time were not only religious, but pushed to their greatness by the strength of their faith.

This God-driven pursuit of science does have a few advantages if it is taken the right way, as it has been with Br. Guy.

“If I think that science is a way of worshiping God, then it means I have to worship truth. And that has to mean that I know I don’t have the truth, because otherwise why would I be looking for it? It has to mean that I’m willing and desirous to listen anybody else who has the truth, whether or not I like what school they went to, or what politics they have.” [SS]

Well, we have come to the end of this fun exercise imagining the inner workings of the top religious and scientific minds of history trying to figure out how they were able to think about the universe. I’ll leave you with a real-world example of why this all matters in a more concrete way, and the consequences it has. If religious people consider the acceptance of science as turning away from God, that can lead to some negative behavior toward the rest of society. Just this week, Br. Guy traveled to Wisconsin to participate in a seminar at Sacred Heart Seminary & School of Theology titled “COVID, Faith, and the Fallibility of Science.”

“In the fight against the COVID pandemic, the scientific evidence in favor of vaccination is overwhelming; but significant sectors of the population, such as many evangelical Christians, have still refused vaccination. This dichotomy has implications beyond vaccine skepticism. The arguments both for and against vaccination too often assume a false view of what science is and what it can promise. The reality of human fallibility, a consequence of original sin, demonstrates our need to accept uncertainty and imperfection in our science and in our religious lives.” [SHS]

“Writing in the New York Times, the Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren suggested that this split [over the vaccine] is evidence of a more general division in our culture between science and religion. She writes, “these past two years have exposed how the science-versus-faith discourse isn’t an abstract ideological debate, but a false dichotomy that has disastrous real world consequences.”” [THW][SHS]

This is a nice and neat example of how Br. Guy is willing to engage in debates outside the usual boundaries of his expertise when he thinks his attention on the topic adds to the overall discourse in a positive way. As a public intellectual, he seeks to have these meaningful conversations with diverse groups of people to try to spread his viewpoint to as many worthy and appropriate areas as possible. He’s doing a pretty great job.

Citations:

[SS] Sixty-Symbols interview. All quotes are from Brother Guy Consolmagno.

Consolmagno, S.J., Guy and Haran, Brady. “The Pope’s Astronomer – Sixty Symbols”. Sixty Symbols, University of Nottingham, February 26, 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0DAKaR16cY. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[LL] Lumen Learning: Scientific Revolution.

Lumen Learning, editor. “Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment.” History of World Civilization II, 2022, courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-tcc-worldciv2/chapter/roots-of-the-scientific-revolution/. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[PR] Professor’s essay on the religious PI.

Mack, Stephen, author. “Wicked Paradox: The Cleric as Public Intellectual.” The New Democratic Review, August 14, 2012, www.stephenmack.com/blog/archives/2012/08/index.html. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[WSJ] Wall Street Journal interview.

Peterson, Kyle. “The Vatican’s Astronomer on God and the Stars; The pope’s chief stargazer, Br. Guy Consolmagno, discusses what the Wise Men saw, how to deflect an asteroid, and why science and faith are more than compatible.” Wall Street Journal (Online), Dec 22, 2018. ProQuest, www.proquest.com/docview/2159713922. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[SCI] Science interview.

Cartlidge, Edwin. “Talking Science and God with the Pope’s New Astronomer: Guy Consolmagno, Director of the Vatican Observatory, Wants to Show That Religion Can Support Astronomy.” Science, vol. 350, no. 6256, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2015, pp. 17–18, www.jstor.org/stable/24749448. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[SHS] Sacred Heart Seminary seminar.

Consolmagno, S.J., Guy, lecturer. “Dehon Lecture: COVID, Faith, and the Fallibility of Science”. Sacred Heart Seminary and School of Theology. February 9, 2022.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=2amYX7oswRQ&t=8s. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[GL] Georges Lemaître.

Soter, Steven and deGrasse Tyson, Neil, editors. “Georges Lemaître, Father of the Big Bang”. COSMIC HORIZONS: ASTRONOMY AT THE CUTTING EDGE. 2000. New Press, American Museum of Natural History. www.amnh.org/learn-teach/curriculum-collections/cosmic-horizons-book/georges-lemaitre-big-bang. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[SP] Space and the Papacy.

Consolmagno, S.J., Guy. “Space and the Papacy.” Religions, vol. 11, no. 12, 2020, pp. 654. ProQuest, doi: dx.doi.org/10.3390/rel11120654. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[JJS] GC’s publication in the Journal of Jesuit Studies.

Consolmagno, S.J., Guy. ” Science of the Vatican Observatory since 2000″. Journal of Jesuit Studies 7.2 (2020): 282-298. doi.org/10.1163/22141332-00702008. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[THW] Evangelical Christians not Vaxxed.

Warren, Tish H. “How Covid Raised the Stakes of the War Between Faith and Science.” ProQuest, Nov 07, 2021, www.proquest.com/docview/2594194609. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[AAS] AAS Carl Sagan Award writeup.

Planetary Sciences Division of the American Astronomical Society. “Guy Consolmagno – 2014 Carl Sagan Medal Recipient”. The American Astronomical Society. 2014. dps.aas.org/prizes/2014. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[VO] Vatican Observatory profile of GC.

Vatican Observatory. “Br. Guy J. Consolmagno, S.J.”. Vatican Observatory. 2022.

www.vaticanobservatory.org/profile/gconsolmagno/. Accessed February 12, 2022.

[SM] Smithsonian Magazine interview.

Ash, Summer. “Guy Consolmagno, the Vatican’s Chief Astronomer, on Balancing Church With the Cosmos”. Smithsonian Magazine. May 31, 2016. www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/guy-consolmangno-vaticans-chief-astronomer-balancing-church-cosmos-180959242/. Accessed February 12, 2022.